Lenses from the ground up

I’ve been working on a Haskell library for Strava’s API. It’s called

Strive. While I was working on it, I encountered an issue that I

didn’t know how to solve. Lenses looked like a promising solution, but I didn’t

understand them. I looked up the most popular lens package (called lens),

and it scared me. Its “field guide” is a massive UML diagram.

I researched lenses for a while and discovered that they’re not that scary. Simply put, a lens is both a getter and a setter. This post aims to be a gentle introduction to lenses using my experience as a motivating example. No advanced Haskell knowledge is required.

Motivation

Let’s start with a basic data type. We’ll also define getters and setters for the fields.

data Athlete = Athlete String

getName :: Athlete -> String

getName (Athlete name) = name

setName :: Athlete -> String -> Athlete

setName (Athlete _) name = Athlete name

blankAthlete = Athlete ""

anAthlete = setName blankAthlete "Taylor Fausak"

getName anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

This works, but it’s tedious. Things get out of control quickly as the number of fields goes up. Let’s change our data type to use the record syntax.

data Athlete = Athlete { name :: String }

blankAthlete = Athlete { name = "" }

anAthlete = blankAthlete { name = "Taylor Fausak" }

name anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

This is great. We didn’t have to write any boilerplate, yet it desugars into what we wrote before. But what happens when we introduce a new data type with the same field name?

data Athlete = Athlete { name :: String }

data Club = Club { name :: String }

-- Multiple declarations of `name'

After desugaring, the getter functions for both fields exist at the top level. One way to get around this is to put each type in its own file. Then you can import them without having multiple conflicting function declarations.

-- Athlete.hs

data Athlete = Athlete { name :: String }

-- Club.hs

data Club = Club { name :: String }

-- Main.hs

import Athlete

import Club

blankAthlete = Athlete { name = "" }

-- Ambiguous occurrence `name'

-- It could refer to either `Athlete.name'

-- or `Club.name'

To us, this looks completely unambiguous. There’s no way we want Club.name

inside of the record syntax for Athlete. It doesn’t make any sense. But to the

compiler, it’s ambiguous. To get out of this mess, we need to use the

fully-qualified names.

-- Main.hs

import Athlete

import Club

blankAthlete = Athlete { Athlete.name = "" }

anAthlete = blankAthlete { Athlete.name = "Taylor Fausak" }

Athlete.name anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { Club.name = "" }

aClub = blankClub { Club.name = "Fixed Touring" }

Club.name aClub

-- "Fixed Touring"

This may work, but it’s annoyingly verbose. We can make it a little better by

aliasing the module names to something shorter. We’ll use A instead of

Athlete, for instance.

-- Main.hs

import Athlete as A

import Club as C

blankAthlete = Athlete { A.name = "" }

anAthlete = blankAthlete { A.name = "Taylor Fausak" }

A.name anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { C.name = "" }

aClub = blankClub { C.name = "Fixed Touring" }

C.name aClub

-- "Fixed Touring"

This is less verbose than before, but it’s still not ideal. If we import a lot of modules, it’s likely that some of them will collide. And if we want to re-export those modules, we can’t do that with the aliases. We can fix these problems, but we have to be more verbose.

data Athlete = Athlete { athleteName :: String }

data Club = Club { clubName :: String }

blankAthlete = Athlete { athleteName = "" }

anAthlete = blankAthlete { athleteName = "Taylor Fausak" }

athleteName anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { clubName = "" }

aClub = blankClub { clubName = "Fixed Touring" }

clubName aClub

-- "Fixed Touring"

Now everything is defined in one module. The names won’t collide because they’re fully qualified. And we can export everything without issue. But we have to repeat ourselves a lot. Fortunately we can add a typeclass to help.

data Athlete = Athlete { athleteName :: String }

data Club = Club { clubName :: String }

class HasName a where

getName :: a -> String

setName :: a -> String -> a

instance HasName Athlete where

getName athlete = athleteName athlete

setName athlete name = athlete { athleteName = name }

instance HasName Club where

getName club = clubName club

setName club name = club { clubName = name }

blankAthlete = Athlete { athleteName = "" }

anAthlete = setName blankAthlete "Taylor Fausak"

getName anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { clubName = "" }

aClub = setName blankClub "Fixed Touring"

getName aClub

-- "Fixed Touring"

We pushed the verbosity into the typeclass, making the usage more succinct. This seems like a perfect solution, but it has one problem: What if the fields don’t have the same type? Let’s say that clubs aren’t required to have names. That means we need to change the data type.

data Club = Club { clubName :: Maybe String }

-- Couldn't match type `Maybe String' with `[Char]'

-- Expected type: Club -> String

-- Actual type: Club -> Maybe String

-- In the expression: clubName

-- In an equation for `name': name = clubName

-- In the instance declaration for `HasName Club'

The HasName typeclass requires that the name field has type String. We

want name to be able to vary from instance to instance. We can do that by

adding another variable to the type class. (And adding the

MultiParamTypeClasses extension.)

{-# LANGUAGE MultiParamTypeClasses #-}

class HasName a b where

getName :: a -> b

setName :: a -> b -> a

Here a is the record type and b is the field type. Since we changed the

definition of our typeclass, let’s update the instances. (We’ll need a couple

more language extensions: TypeSynonymInstances and FlexibleInstances.)

{-# LANGUAGE TypeSynonymInstances #-}

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleInstances #-}

instance HasName Athlete String where

getName athlete = athleteName athlete

setName athlete name = athlete { athleteName = name }

instance HasName Club (Maybe String) where

getName club = clubName club

setName club name = club { clubName = name }

Let’s see what happens when we use this new code.

blankAthlete = Athlete { athleteName = "" }

anAthlete = setName blankAthlete "Taylor Fausak"

getName anAthlete

-- The type variable `a0' is ambiguous

This looks like it should work, but it doesn’t. The return type of getName is

ambiguous. This is because the variables in the HasName typeclass are

independent. We can work around this problem by specifying the types.

getName anAthlete :: String

-- "Taylor Fausak"

This does what we want, but it’s ugly. Our typeclass is giving us flexibility we don’t need. That’s forcing us to be explicit about our types. Let’s define another instance to highlight the flexibility of the typeclass.

instance HasName Athlete (Maybe String) where

getName athlete = Just (athleteName athlete)

setName athlete maybeName = athlete { athleteName = maybe "" id maybeName }

getName anAthlete :: Maybe String

-- Just "Taylor Fausak"

This is an interesting concept, but it’s ultimately useless for our purposes. We

want each input type, like Athlete to be uniquely paired to an output type,

like String. This is possible by adding a functional dependency to the

typeclass.

{-# LANGUAGE FunctionalDependencies #-}

class HasName a b | a -> b where

getName :: a -> b

setName :: a -> b -> a

This says that b depends solely on a. What this means for us is that given

a, we already know b. For instance, given that a is Athlete we know that

b is String. This allows us to avoid explicit type annotations.

getName anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { clubName = Nothing }

aClub = setName blankClub (Just "Fixed Touring")

getName aClub

-- Just "Fixed Touring"

This is pretty great. We’ve got short getters and setters that are easy to use and type safe. What more could you want?

Lenses

It’d be nice if the getters and setters weren’t prefixed with “get” and “set”.

Let’s take a step toward that by defining two new functions called get and

set.

get :: (a -> b) -> a -> b

get getter record = getter record

set :: (a -> b -> a) -> a -> b -> a

set setter record field = setter record field

Ignore the fact that these are both synonyms for id. We’ll come back to that

later. Let’s see how you’d use them.

blankAthlete = Athlete { athleteName = "" }

anAthlete = set setName blankAthlete "Taylor Fausak"

get getName anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { clubName = Nothing }

aClub = set setName blankClub (Just "Fixed Touring")

get getName aClub

-- Just "Fixed Touring"

This is worse than before! Instead of removing “get” and “set”, we’ve repeated them. But not without reason; these two functions make up a lens. We can define a new type to hold them.

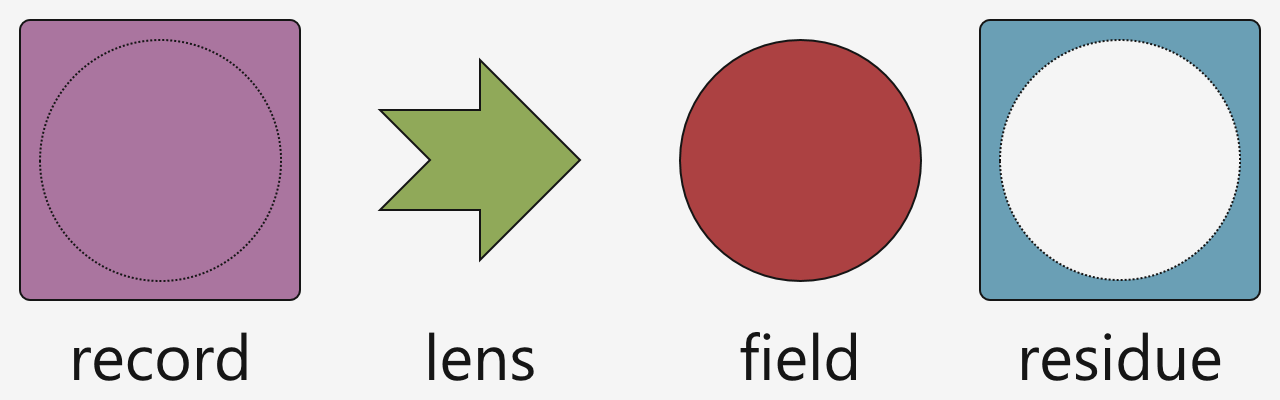

data Lens a b = Lens

{ get :: a -> b

, set :: a -> b -> a

}

That type represents the core idea of lenses. Let’s use it to define lenses for our types.

athleteNameLens :: Lens Athlete String

athleteNameLens = Lens

{ get = \ athlete -> athleteName athlete

, set = \ athlete newName -> athlete { athleteName = newName }

}

clubNameLens :: Lens Club (Maybe String)

clubNameLens = Lens

{ get = \ club -> clubName club

, set = \ club newName -> club { clubName = newName }

}

We can use these lenses to redefine our typeclass along with its instances.

class HasName a b | a -> b where

name :: Lens a b

instance HasName Athlete String where

name = athleteNameLens

instance HasName Club (Maybe String) where

name = clubNameLens

Finally, we can use this new typeclass to write shorter, cleaner code.

blankAthlete = Athlete { athleteName = "" }

anAthlete = set name blankAthlete "Taylor Fausak"

get name anAthlete

-- "Taylor Fausak"

blankClub = Club { clubName = Nothing }

aClub = set name blankClub (Just "Fixed Touring")

get name aClub

-- Just "Fixed Touring"

I think you’ll agree that this is the best version of the code so far. It doesn’t use verbose names and it doesn’t require multiple modules or aliased imports. That’s the power of lenses.

Further reading

If you’re looking for more, Jakub Arnold’s Lens Tutorial is an excellent follow up. It starts with simple lenses like those introduced here and derives functor-based van Laarhoven lenses from them.

If you’re interested in more information about the lens library, I suggest you

read A Little Lens Starter Tutorial by Joseph Abrahamson. It starts with

lenses and goes on to cover prisms, traversals, and isomorphisms.